Wheeler Penal Colonisation

THE PENAL COLONISATION OF AUSTRALIA (1788 - 1868). PART 1: INTRODUCTION By Chris Wheeler

The inspiration behind these articles comes mainly from the lengthy novels by the Australian authors Nancy Cato, Lola Irish and Colleen McCullough, with support from Wikipedia and Stanley Gibbons.

The forced exile from a society has been used as a punishment since Ancient Roman times. It reached its height in the British Empire during the 18th and 19th centuries. It removed the offender from society, and was seen as more merciful than capital punishment. This method was used for criminals, debtors, and military and political prisoners. Penal transportation was also used as a method of supporting colonisation and increasing the labour  force. For example, from the 1820s until the 1860s, convicts were sent to Bermuda to work on the construction of the Royal Navy Dockyard and other defence works, including an area still known as “Convict Bay” at St George’s Town, and to other Caribbean Islands such as Barbados to work on developing the sugar cane farms and the building of villages and storage facilities.

force. For example, from the 1820s until the 1860s, convicts were sent to Bermuda to work on the construction of the Royal Navy Dockyard and other defence works, including an area still known as “Convict Bay” at St George’s Town, and to other Caribbean Islands such as Barbados to work on developing the sugar cane farms and the building of villages and storage facilities.

Many convicts were shipped to the eastern States of the newly developing USA, which were then a colony of Great Britain. Many other countries were also trying to establish colonies in this ‘new land’ which led to conflict and the French and Indian War (1754-1763), which some see as the American portion of the Seven Years’ War. One of the primary causes of the war was increasing competition between Britain and France, especially in the region of the Great Lakes and the Ohio Valley. It was settled in the Treaty of Paris (1763), when France formally ceded to Britain the eastern part of its vast North American Empire, thus formally ending the conflict and confirming the new nation’s complete separation from the British Empire. However, this newly developing USA wanted complete independence, which led to the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) when the British were defeated. One of the obvious results of this defeat was that alternative destinations had to be considered for banished convicts. Some 60,000 Loyalists had migrated to other British territories, particularly to British North America (Canada) to continue the struggle. Many of these were arrested and sent to Great Britain and ended up as convicts on the First Fleet to Australia.

After the termination of transportation to North America, British prisons became overcrowded, and dilapidated ships moored in various ports were pressed into service as floating gaols known a “hulks”. Some of the convicts had been imprisoned for very minor offences, such as pilfering. Warning signs were displayed everywhere. Following an 18th century disastrous experiment in transporting convicted prisoners to Cape Coast Castle (modern Ghana) and the Gorée (Senegal in West Africa), British authorities turned their attention to New South Wales, for at this time Captain Cook and others were returning from their discoveries of Australia, which appeared to be a largely uninhabited continent with potential as a new colony and penal location. Although much further away, Australia was decided upon.

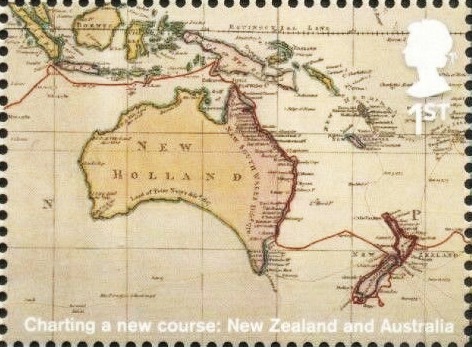

Several Europeans had landed or circumnavigated Australia before Captain Cook started his voyages. Captain Cook had previously discovered the Northern Route across the top of Australia in HMS Endeavour on his way to New Zealand. It was on his third visit to the Pacific Ocean, on 29 April 1770, that Botany Bay was the site of his first landing of HMS Endeavour on the land mass of Australia. Cook recorded in his diary that “The great quantity of plants Mr Banks and Dr Solander found in this place occasioned my giving it the name of Botanists (Botany) Bay”. Earlier that day he had written in his journal “at noon we were about 2 or 3 miles from the land and abreast of a bay or harbour within which there appeared to be a safe anchorage which I

Several Europeans had landed or circumnavigated Australia before Captain Cook started his voyages. Captain Cook had previously discovered the Northern Route across the top of Australia in HMS Endeavour on his way to New Zealand. It was on his third visit to the Pacific Ocean, on 29 April 1770, that Botany Bay was the site of his first landing of HMS Endeavour on the land mass of Australia. Cook recorded in his diary that “The great quantity of plants Mr Banks and Dr Solander found in this place occasioned my giving it the name of Botanists (Botany) Bay”. Earlier that day he had written in his journal “at noon we were about 2 or 3 miles from the land and abreast of a bay or harbour within which there appeared to be a safe anchorage which I  called Port Jackson”. Naturalists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, and artist Sydney Parkinson spent several months from April 1770 collecting and sketching the flora and fauna they found there. The land was subsequently claimed for the British Crown on the basis that it was terra nullis, or empty land. Of course, this was a fallacy as the Torres Strait Islander peoples had been living on the land for some 60,000 years. This eventually became the first European settlement for convicts on the Australian mainland, but due to its then inhospitable conditions, this penal settlement was almost immediately moved across the Paramatta River to Sydney Cove.

called Port Jackson”. Naturalists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, and artist Sydney Parkinson spent several months from April 1770 collecting and sketching the flora and fauna they found there. The land was subsequently claimed for the British Crown on the basis that it was terra nullis, or empty land. Of course, this was a fallacy as the Torres Strait Islander peoples had been living on the land for some 60,000 years. This eventually became the first European settlement for convicts on the Australian mainland, but due to its then inhospitable conditions, this penal settlement was almost immediately moved across the Paramatta River to Sydney Cove.

Thus, on 13 May 1787, what became known as the “First Fleet” consisting of eleven ships and about 1,530 people (736 convicts, 17 convicts’ children, 221 marines, 27 marines’ wives, 14 marines’ children and about 300 officers and others) under the command of captain Arthur Phillip set sail from England. These convict ships in the First Fleet manned by the Royal Navy were sent in convoy, taking about a year for the journey, via Tenerife, Rio de Janeiro and Cape Town, then across the South Atlantic and Bass Strait to Sydney, using the prevailing winds as best as possible and re-stocking at each port of call. Conditions on board were horrendous and many died. Eventually, on 26 January 1788 they reached and established a settlement at Sydney Cove. This date later became Australia’s National Day – Australia Day. The colony was formally proclaimed with the raising of the British Flag by Governor Phillip on 7 February 1788 at Sydney Cove, although James Cook had proclaimed sovereignty over Australia from the shore of Possession Island in 1770.

The First Fleet which established the first colony was an unprecedented project for the Royal Navy, for it had a dual role in establishing a military base in the Pacific to deter the French. The Colony of New South Wales, which included the whole of Australia and New Zealand, was thus established in 1788 as part of the British Empire. Over subsequent years, further Fleets arrived and self-governing States were created, reducing the size of New South Wales, and New Zealand became an independent country. This later period also saw the introduction of stamps, vehicles and planes. Until then ships made irregular trips back to Great Britain, so there was little communication, especially from the convicts who were not allowed to write until they were freemen.

At each stage, the Aborigines lost their indigenous and itinerant life-style, became second class citizens, and having lost their traditional way of life obtained their livelihood as servants and slaves, lacking education and spending the little they earned on poor-quality food and subject to the dangers of alcohol. This is now changing as attitudes and appreciation of what has happened to them is being recognised.

As the years passed, penal colonies were established up the east coast of Australia, at Port Macquarie, Moreton and in Queensland, as well as on Norfolk Island, Tasmania and finally along the Swan River (Fremantle) on the west coast. These will be the subject of later articles.